#94 MY GREAT-GRANDMOTHER--A FINNISH HOMESTEADER

MINNI (KAJANDER) HENDRICKSON

Ping the

air tag on my cat’s collar and I can find Jeremiah’s exact location, within

feet, in the back yard. A GPS makes navigating European back roads or city streets, round-abouts or unmarked laneways less stressful; and it can take you

to an exact address with travel alerts en route. Get on a modern, safe airplane, comfortably settle into the on-board entertainment, be served meals and drinks and, within hours, arrive at a destination anywhere in the world. Key in a foreign text to

Google Translate to get an immediate and accurate summary of a text,

or use it to get common phrases and travel language (hello, thanks, please, washroom,

how much? etc.) Cell phones, Facetime, the internet, give instant global

communication with family, friends and businesses. Foreign currency is accessible at ATMs or, simply, just go cashless and use a credit/debit card.

This is the age in which we live and all the tools we take for granted when we travel. And that’s why I am in complete awe of my great-grandmother, Minni (Kajander) Hendrikson who, in 1905, emigrated 7,000 km (4300 miles) from Finland to the US Midwest. Her husband, Jalmar, had preceded her to North America; Minni followed him the next year. She knew very little English (in fact Finnish has a completly different language base and is quite different in grammar structure and word origins and is a difficult language to master). Minni had likely never travelled far from Turku, she had little money, and was emigrating with just her three year old daughter, Karina.

How daunting and scary each of these challenges! Her

plan was to meet up with Jalmar in North Dakota where he had found work as a

farm labourer. How exactly (without cell phones, GPS, language skills, geography

knowledge) would she even know where he

was, is a mystery, too. How would he know when and where to meet her? What if he

failed to meet her or something had happened to him? And I cannot even imagine

Minni’s anxiety travelling solo with a young daughter aboard ship and then rail

in a foreign world! She must have been so worried about her child’s health and

safety. How could she ensure that strangers were giving her honest advice along

the way?

Wilhelmina

Josephina Kajander was born June 24 1877 in Finland, which then was an autonomous

Grand Duchy of Russia. Jalmar was born April 8, 1878. They were married about

1900 in Turku (Abo). A son, Niilo Elmar, died in January 1901, a month after

his birth. Daughter Karen Wilhelmina (sometimes called Karin or Katherine but

most commonly known as Carrie) was born April 5, 1902.

Large-scale

emigration from Northern Europe began in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries when the traditional Finnish agricultural economy

conflicted with fundamental demographic changes. In the early 20th

century, 70% of the Finnish population was agricultural and stability was being

undermined by a population growth which had risen from 863,000 people in 1812 to

over 3 million by World War 1. The resulting overpopulation was impacted by existing

laws that land could not be divided among heirs; even in large

families, only one child could inherit, while the other siblings had to earn a

living some other way. Industry and small Finnish towns were unable to provide

enough work, and thus emigration was inevitable for many of the landless

population. By the late 1800s, American Fever—the appeal of free homesteads,

plentiful work in mines, railways, lumber camps—spread through the eastern

provinces of Finland and became the main reason for leaving. Emigration

peaked in 1902 when crops failed and Russian Imperial forces threatened to

conscript young Finns into the Russian army. Between 1880 and 1910, over a

quarter million Finns emigrated to North America. The Hendriksons were one of

those families.

Jalmar emigrated early in 1904 and later that year, Minni and three-year-old Carrie followed. Most likely mother and young daughter went by steamship from the port of Hanko, Finland to Hull England where upon arrival, they typically remained on board until their connecting train was ready to transport them across England. Trains departed from Hull's Paragon Railway Station and traveled directly to major ports like Liverpool. At times, the number of emigrants arriving in Hull was so large that trains with up to 17 carriages were required to accommodate both passengers and their baggage. These trains usually left Hull on Monday mornings around 11 a.m., arriving in Liverpool between 2 p.m. and 3 p.m where emigrants would board the transatlantic liners bound for North America.

Minni and Carrie sailed on the S.S.Parisian, a ship built in 1881 for the Allan Line and was the first North Atlantic mail steamer built of steel. There was accommodation for 150 First-class, 100 Second-class and 1000 passengers in steerage. Minni and Carrie travelled steerage and paid roughly $10 (about $300) for their passage. At that time the average ocean crossing from Liverpool to North America took about a week; mother-daughter landed in Halifax on January 15, 1905. (Interestingly, just 2 months later, on March 25, the Parisian, while at standstill was rammed in Halifax harbour by a German ship and it was said the hole was big enough for a man to walk through. In 1912, the Parisian took part in the search for victims of the Titanic disaster.)

The Parisian

Jalmar was in North Dakota working as a farm labourer. He sent money to pay for their passage. Minni and Carrie travelled third-class from Halifax to Winnipeg aboard a CPR colonist car. Colonist cars were designed as boxcars which could then be converted to grain cars for the trip back east. Passengers could travel from Montreal to Vancouver for $25 but had to pay extra for food, blankets, pillows, even berth curtains. The CPR famous wool blankets were rented out at a dollar each, the same price as a mattress. Pillows went for 35 cents each and berth curtains, for privacy, cost a dollar a pair. Most immigrants on tight budgets, as Minni was, did without the frills and spent several days in cramped quasi-comfort. Snacks were heated on the car’s kitchen range at the end of the passenger compartment across from the ladies’ room. Coal-burning stoves at each end of the car provided heat. The average temperature in Winnipeg in January 1905 was -20 C (-4F◦).

CPR Colonist car

On January 15, 1905 Minni and Carrie crossed form Manitoba into North Dakota. She had $17 in her possession. Jalmar met them in Rollo, North Dakota. Alone, caring for a toddler, all those many miles, little money, strange language! How relieved she must have been to have safely made it!!! A son, Aimo, was born that September. 😉(winking emoji)

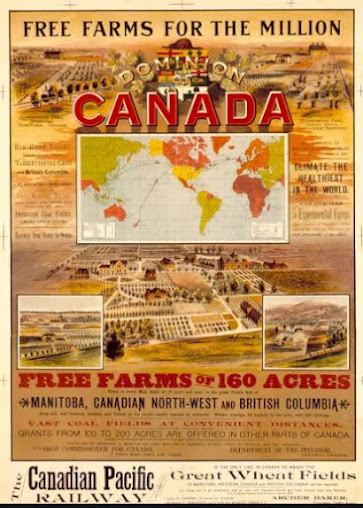

Towner Township, North Dakota...so flat..dirt roadsWhile Jalmar worked as a farm labourer in Towner Township, Minni and the children boarded nearby; perhaps, like many Finnish women, she was working as a domestic or seamstress. In 1911, the Hendriksons joined the thousands of immigrants heading to Western Canada seeking opportunity. The Canadian government, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was keen to populate the West with hardy farmers who would grow wheat for export and thus contribute to the national economy; a settled West would also solidify Canada’s claim to sovereignty over the northwest. Ottawa had surveyed the land and had negotiated treaties with First Nations and confined them to reservations. Completion of the C.P.R. in 1885 meant easier transportation of people, wheat and manufactured goods. Settlement of Canadian Prairies began in earnest in 1896. The population of Saskatchewan grew from 91,000 in 1901 to 492,000 by 1911, making it the third most populated province in Canada.

The Hendrikson family left North Dakota on July 5, 1911 via

the Grand Northern R.R. and crossed into Manitoba at Bannerman, Manitoba. It

seems like Jalmar had again preceded his family as only Minni, Carrie and Aimo

are listed on the border crossing.

Hundreds of thousands of square miles of Canada’s Prairies had been surveyed into a grid system of townships, sections and quarter sections. Each township had numbered sections from 1 to 36. To encourage settlement, the Canadian government offered a free homestead of 160 acres. The only cost was a $10 ($250 today) registration fee. To qualify for a land patent, the settler had to be male, aged 21 or older (or a woman who was the sole support of a family), and a British or naturalized British subject. The applicant had to reside on the homestead for at least 3 years and for 6 months of each of those 3 years, erect a house with a minimum size of 18’ X 24’ and worth at least $300, cultivate between fifteen and fifty acres by removing all rocks, stones, trees and stumps and then plant at least ten to thirty acres of crops. A fireguard to protect farm buildings had to be plowed. And all these conditions had to be met within the first three years.

Hendrikson homestead todayJalmar was granted the Northeast quarter of section 34 in Township 25, Range 12, west of the third Meridien, King George Municipality, Saskatchewan. Wiseton was the closet village. Jalmar built a small frame house and stable, dug a well, purchased livestock, broke the land and cropped about 32 acres. Most of the native prairie grass was broken by homesteaders using wooden plows powered by oxen or horses; later a single or two furrowed riding plow came out and this gave the operator unheard of comfort.

oxen teambinder 1927--Wiseton

Around 1920, huge steam tractors pulling twelve or fourteen plows were used. The fields were disced and seeded; the crop was harvested with a horse-drawn binder which cut the wheat, and tied it into sheaves; after the wheat had cured and dried, it was ready for threshing. The grain was taken to the elevators in Wiseton to await shipping.

Jalmar, but not his wife or children, was naturalized in 1914. Jalmar worked hard and on June 12, 1916, he received the land patent for his homestead; he later purchased another quarter section.

Settlement often seems to be the man’s story. But Minni had already shown an undaunted spirit when she emigrated. Minni must have had an extraordinary combination of resilience, resourcefulness and determination. She must have been incredibly strong, both physically and mentally, to endure long hours of hard labour and cope with the prairie isolation. Practicality was essential--she had to be adaptable, quickly leaning how to fix things, grow food and make do with limited resources. Patience and perseverance were needed to face challenges of weather, illness, and unpredictable harvest. Survival as a pioneer woman demanded a fierce, enduring spirit and an unwavering commitment to her family and the land.

Bread was the primary food at every meal and women baked it at least twice a week. Food preservation was important because refrigerators were non-existent so perishable food had to be stored in the cellar, a dugout room below the house where the ground kept the temperature cooler. Foods such as milk, butter, cream, and vegetable would be stored there. Beets and carrots would be packed in containers of sand to be stored in the cellar over the winter. Farm homes had large gardens. When sod was first broken, potatoes were the only thing planted in the garden. Meat preservation was also necessary—whether it was curing ham and bacon, freezing sausages, preserving pork in crocks of lard. Garden vegetables and fruit were often canned. Women also churned butter and gathered eggs. Saskatoon berries were a a pleasant change from dried fruit.

Without modern conveniences, daily tasks like cooking over a wood stove, hauling water, and preserving food took up much of the woman's time. Washing clothes was done by hand with, perhaps, a hand-turned wringer; water was heated on the stove. Pioneer women, like Minni, had to be hard-working, self-sufficient and organized. One prairie wife wrote: Then I wash the dishes, sweep the kitchen, and am ready for sewing. The little boys’ clothes I buy ready-made, but not other things as I think poorly-sewed readymade things only rip out and add to the sewing, besides they never look neat or well made. I churn twice a week and that has to be done in the afternoon as there is never time in the forenoon, and that takes one hour each Wednesday and Friday afternoons. I churn in the cellar, wash and salt the butter...and pack it in the crocks. Then the rest of the afternoon is free for mending and sewing. Then the children come home from school and I have help. They mind the baby, hunt the eggs, bring up the cows…We have supper in summer at seven and I wash the dishes, and the little boys bring in the kindlings and night wood…while the men finish the chores, I set the table, grind the coffee, cut the meat, set the pancakes and the day’s work is done with a few minutes of twilight to read before bedtime…I wash Mondays; the boiler is put on right after breakfast...then we rinse , starch and get the clothes on the line before dinner time. Then I have the kitchen floor to clean. Saturday is a busy day with but few minutes to rest. Baking takes up most of the morning The little folks have to be bathed and all the little extras to be done in view of Sunday being a day to read and rest, with everything cooked for the meals, dish-washing being the chief work of the day. And many women also helped the men with fieldwork.

Mail was the only means of communication and it didn't come often; "word of mouth", because of the sparsely settled area, was infrequent and not always reliable. Homesteading was a lonely life, particularly in the long, cold winter months and there was little entertainment or social life in those early years. Medical care was scarce. There were no church services, until some were held in homes; the first school in Wiseton was built in 1914. Children had few pastimes in the early homestead years, perhaps one of the more common being the trapping, drowning or snaring of gophers for a one cent bounty per tail.

Both Jalmar and Minni died on their homestead. Minni passed on July 1, 1927, aged 50. “After a service at the home…a cortage of over 35 cars followed the remains to the Mosten Cemetery where the Rev. F.Schwartz, Pentacostal Mission, conducted the burial service and led the singing.” Jalmar, aged 50, died [sic:dropped dead] the next year on August 19, 1928 from a heart attack. (Jalmar's farm was assessed at $3500; he willed 2/3 to his son and 1/3 to his daughter, my grandmother,)

Unfortunately, there are no known photos of Minni (or

Jalmar)---even more reason to make sure her intrepid spirit is remembered.

Jalmar Hendrikson b . Apr 8 1879 in Tampere, Finland d. Aug 19 1928 Saskatchewan my maternal great grandparents

Beautifully written Carole - so much research! Deb McA

ReplyDeleteThey were such strong and determined ancestors you had...that strength and determination and consistency of purpose is a gene I am sure you inherited. We share ancestors in Sask who when out west to farm and try to establish successful farms and families. My went to Star City and Melfort...on town Herbert is named after a great Uncle. What a difficult life style so endured by all who took the journey in the interests of a better life and future for them and their children.

ReplyDeleteLove your stories and the research of the times and time period they experienced. Verna

Undaunted courage and hard work was needed to achieve what Minni and Jalmar were able to do.

ReplyDelete