#80 A CIVIL WAR SOLDIER

LAFAYETTE McCARTY

Death

has again crossed the threshold of another home in our midst and clasped in icy

fetters one of our oldest citizens. On last Saturday evening, February 2, 1895,

as the day was dawning to a close, the spirit of Lafayette McCarty broke its

frail barrier of clay here on earth and winged its way to the realms of the

infinite. --The Lane

Graphic, Kansas, Feb 8, 1895.

Lafayette McCarty was born in Vermont in 1823 and while still a child moved with his parents first to New York, then on to Ohio where he grew up. In 1851, he married Belinda Peake and they had eight children, four of whom reached adulthood. In 1860, Lafayette, aged 34, was listed as a shipbuilder in Brownhelm, Ohio; large lake schooners were being built there for shipping on the Great Lakes.

The American Civil War began April 1861 and was caused by deep-rooted tensions over slavery, economic differences and political power. The moral and economic conflict over slavery was central; the Southern states relied on slavery for their agricultural economy, while the more industrialized Northern states increasingly opposed it. Tariff and trade policies often benefitted the industrial North at the expense of the agricultural Southern economies. Southern states argued for the right to govern themselves, including the right to allow slavery. As new states joined the Union, there were heated debates over whether they would be slave or free states as this would tip the balance of power in Congress; Southern states feared losing influence. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 was seen as anti-slavery and was the trigger that prompted Southern states to secede from the Union and led to the outbreak of the Civil War.

On October 11, 1861, Lafayette, age 38, enlisted with the newly-formed 72nd Ohio Volunteer Regiment. The 72nd Ohio was formed in August 1861; the first recruits were farmers, labourers and young men eager to serve the Union cause. (Ninety-five percent of Union soldiers were volunteers.) Training was brief and soldiers quickly learned the basics of military drill, marching and weaponry, but they were unprepared for the realities of military life—long hours of drills and little idea of the reality of battles.

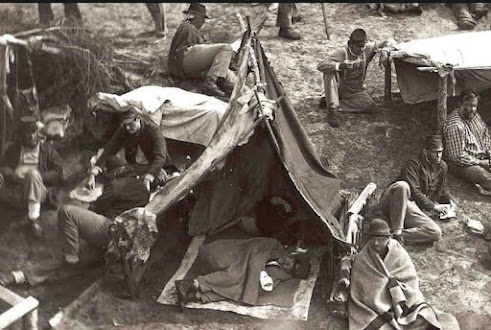

Camp life for the 72nd was governed by strict military discipline. Soldiers woke early and began the day with roll call and physical training and then drills which could last several hours. Soldiers had to look after their own uniforms, weapons and gear. Basic food rations were poor and included hardtack (a dry biscuit), salted pork or beef, beans, coffee, and sometimes dried fruit. The quality of food depended on location and supply lines, but a constant complaint was the monotony and the lack of fresh food. Soldiers slept in tents, which were cramped and offered little protection from the weather. Hygiene was a significant issue and poor sanitation led to the outbreak of diseases such as dysentery, malaria and typhoid. Medical care was rudimentary; field hospitals were poorly equipped and doctors had limited knowledge of sanitation and infection.

Lafayette mustered in February 1862. The 72nd Ohio was deployed along the Mississippi on the Western frontier. Its first combat in April 1862 was the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, one of the war’s bloodiest and most intense engagements. The horror of battle—hearing gunfire, artillery explosions and seeing casualties—was a brutal initiation for the 72nd. The Regiment fought in fierce conditions and suffered significant casualties, but this battle helped secure Union control in the West. Then (May 1862) the 72nd fought in the siege of Corinth, a strategic railroad town in Mississippi.

From there

the Union army could strike at the Confederate army for control of the

Mississippi River Valley. Vicksburg had kept the river closed to Union commerce and

traffic and it was the last place where Confederate troops could pass good and

troops to the south. In May 1863, the Northern army encircled the town and

drove its defenders inside the town’s fortifications; the town was besieged for

more than forty days, no food or ammunition could get in, civilians were

reduced to eating mules and rats. After more than a month of hunger, repeated

attacks and shelling by Northern forces, the Confederates surrendered. The 72nd

Ohio Regiment contributed to the siege efforts.

In March

1864, Lafayette McCarty “promptly reenlisted as a veteran determined to see the

war through”. Three months later, in June 1864, Confederate forces attacked the Union

garrison at Young’s Point, a fortified position along the Mississippi River but

the Union forces, including the 72nd Ohio, were able to defend their

position and repel the attackers. The Battle of Young’s Point was more of a

skirmish than a full-fledged battle but victory here was needed as Union forces

moved towards larger objectives in the South including Sherman’s Atlanta

Campaign and eventual March to the Sea.

Unfortunately,

Lafayette McCarty was captured in this skirmish on June 4 and was taken to Andersonville

prison camp in Georgia. Built to house Union prisoners of war, Andersonville quickly

became infamous for its severe overcrowding, unsanitary conditions and high

mortality rate. Designed to hold around 10,000 men, the prison population

swelled to over 30,000, leading to a shortage of food, water and adequate shelter.

Prisoners were confined within a 16 acre, open-air stockade, which lacked

sufficient barracks, leaving most exposed to harsh weather. The camp was

surrounded by a 15-foot-high wooden wall with a "dead line" — an

inner boundary that, if crossed, would result in guards instantly shooting the prisoner.

Most prisoners had no shelter beyond makeshift tents, known

as "shebangs," made from scraps of cloth, sticks, or whatever

materials they could scavenge. Lacking adequate clothing and blankets, prisoners were exposed to the elements--scorching summers, torrential rains,

and, at times, chilling nights.

Food rations were meager and nutritionally inadequate, often

limited to small portions of cornmeal or occasionally rancid pork, and

prisoners rarely received vegetables or other vital nutrients. Malnutrition was

rampant, and many suffered from scurvy, a painful disease caused by a vitamin C

deficiency. Hunger became an overwhelming preoccupation for the prisoners, as

they struggled to survive on the scant food provided. The prison's single water

source, a narrow stream known as Stockade Branch, flowed through the camp but

quickly became contaminated with human waste due to a lack of sanitation and

drainage. This polluted water caused outbreaks of dysentery, diarrhea, and typhoid

fever, which spread rapidly in the crowded camp. Medical care was virtually

nonexistent, and the few available doctors had limited resources and supplies,

leaving prisoners to die from treatable infections and illnesses. Disease,

starvation, and exposure killed an average of about 100 men each day at the

prison’s peak.

Prisoners formed informal groups or "messmates" to

share limited resources and provide each other with support, but desperation

and despair often led to theft, fights, and even murder over food and supplies.

Despite the dire circumstances, some prisoners showed remarkable resilience,

creating a makeshift justice system called the "Regulators" to deal

with crime within the prison. Spirituality and camaraderie provided solace for

many, as did stories of their families and dreams of freedom.

Lafayette McCarty was imprisoned at Andersonville for five months.

What horrors he saw and experienced! Prisoners faced not only the physical

challenges of survival but also a psychological struggle against hopelessness

and despair. An estimated 13,000 deaths

at Andersonville during its operation, made it one of the deadliest sites in

Civil War history.

Andersonville Prison 1864

On November 19, 1864, McCarty was freed as part of a prisoner exchange and “frequently we have heard him tell of the joy there was on board the fleet that bore him back to the north, the home of the stars and stripes.” The US Civil War ended in April 1865 and the 72nd Ohio was mustered out. For many, this was a time of relief but also of adjustment as these Soldiers had witnessed or experienced things that would haunt them the rest of their lives. They returned to civilian life, but the physical and psychological scars remained.

Lafayette was honorably discharged in June 1865. He returned to Ohio and reunited

with his wife and three children. Five more children followed, although only

four reached adulthood.

Kansas become a state in 1861 and many frontier towns sprang up. Settlers were attracted by the good soil and the chance to homestead 160 acres of free land granted by the federal government. Its railroads were destinations for the Texan cattle drives which then shipped the cattle to markets in the east. Farmers first tried to grow corn and raise pigs, but this failed because of the lack of rain; the solution was to switch to wheat. Kansas was home to many Wild West figures, including Wild Bill Hickock, Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp and the Dalton gang. The decade of the 1870s was quickly changing Kansas from a windswept open prairie to America’s agricultural heartland.

Kansas homesteads

In the spring of 1877, McCarty purchased farmland and moved his family to Kansas.

In 1888, Lafayette was granted a civil war pension. To

qualify, a veteran needed to have served in the Union Army for at least 90 days

(Lafayette served 3 years, 9 months), received an honourable discharge, and

have a disability that didn’t stem from “vicious habits.” The pension amount

ranged from $6-$12 a month. Running this pension programme was a big government undertaking. Pensioners' claims had to validated by checking old military service

records, sending special examiners to interview people who had known the

claimant, arranging medical examinations, then determining the amount of the

pension. This created a lot of record-keeping. Forty-one percent of all northern

men born between 1822 and 1845, (like Lafayette) served in the Union Army. (60%

of those born 1837-1845; 81% born in 1843) Initially, pensions were paid according

to the degree of disability (ie. the inability to perform manual labour requiring severe

and continuous exertion.)

In 1893, Lafayette was elected a Republican trustee of his district to oversee road construction.

It looks like Lafayette and Belinda were of the Quaker faith

and members of the Lane, Kansas church, which had been founded there in

1855. It’s uncertain what that religion’s appeal was to the McCartys—its views on Christian love, anti-slavery, temperance, unbecoming behaviour,

talebearing (gossip), simplicity, peace, community, worship in quiet, no

clergy, no sacraments, no oaths, no hymns, pacificism, equal treatment of

women. Quakers are officially known as the Religious Society of Friends and

members are called Friends.

Lafayette McCarty died February 2, 1894, aged 70. For the previous six months, he had been quite ill, the result of illness contracted while in the army. His funeral service was held in the Quaker Church and he was buried in the old Spring Grove Quaker Cemetery.

Belinda McCarty was eligible to receive her husband’s war

pension. Belinda died, aged 83, on June

25, 1915; she had been nearly blind for her last eight years and an invalid for

the last year. She was buried beside her husband in the Spring Grove Quaker

Cemetery.

LAFAYETTE M. McCARTY b. Jul 6 1823 in Vermont m. Belinda Peake (1831-1915) on Nov 7, 1851 in Erie, Ohio d. Feb 2 1895 in Lane County, Kansas father-in-law of my 1st cousin 3x removed (Pierson line)

Comments

Post a Comment