#59 MY CORNWALL FARMING FAMILY

John & Grace Lemin

My 3x great-grandfather, John Lemin lived his entire 76

years (1785-1861) in the Parish of Warleggan, County Cornwall. In April 1807, he married Grace

Oliver in St. Bartholomew’s Church, Warleggan and it was in that same rustic church that all six of their children were baptised. Grace died in 1843 (age

64); shortly after, John married Jane Cole Henwood.

I think of how John would be stunned by today’s

world—technology, transportation, communication, medicine, politics, religion. He

likely never travelled more than a few miles from his home. He likely never

learned to read or write. The concepts of

“retirement” and “pensions” and

“leisure-time” would have been so foreign to him. Life was always a precarious struggle and agricultural workers,

like John, were the poorest of the poor.

By Tudor times, the English aristrocracy was acquiring larger estates and enclosing or fencing off the common land. Deprived of this pasture land where they had grazed their stock, the peasant farmers were forced to abandon their farmed strips; this class of landless men were now forced to work the land of the rich landowners.

There were two types of farm workers—farm servants and agricultural

labourers. Farm servants worked around the barn buildings and they had to renew

their contracts every 6, 9 or 12 months. Agricultural labourers were employed

annually to work the farm land; they were more often married, more settled and

lived in cottages on the perimeter of the farm; they were paid weekly and had

fixed hours of employment. Farm labourers often prepared, manured and looked

after a small portion of the farmer’s property and in return were able to grow

a few potatoes for food. (like in Ireland, Cornwall was hard hit by the potato

blight in the 1840s.) The common practice of the time, the potato allotment,

was an agreement where no money changed hands and that was made between the

labouring farm hand and the farmer; labourers could, however, receive beer

instead of wages.

My great-great-great grandfather, John, was an agricultural worker, a somewhat more secure job than a farm servant. Nonetheless his days were long, his pay low and the family lived close to poor relief or the workhouse and in constant fear of the breadwinner’s death or illness or injury which would throw the family into desperation.

A typical day for John began before dawn when the labourers would walk to the farmhouse to receive the day’s instructions. Once in the fields, they would often be joined by the women and children. The women would drive the cows, sow seeds, and sometimes drive the plow. The children would pick fruit, or weeds or stones from the fields. (It was not until 1867 that a law was passed forbidding the use of children in agricultural gangs.) Lunch break was either a Cornish pasty (cooked food wrapped in a pastry for easy carry) or a ploughman’s lunch (cheese, fruits, bread wrapped in cloth).

The work ended at dusk. If the work was seasonal, there might be times of no work and thus no daily pay. Most families tried to supplement their income with cottage industries like straw-plaiting, lacemaking, knitting, basketry, glove-making.

Harvest was the busiest time. Hay crops were cut with a scythe in early summer. Wheat was harvested in late July and barley, the main crop, in September. The men would cut the crop with a scythe and the women would follow, pick up the cut grain and bind it into sheaves. A skilled scythe-man could cut a couple of acres a day. The dried crop would be taken to the farmyard and laid over “ricks” and stone foundations designed to protect from the rats. Finally, there would be the Cornish ceremonial “crying the neck” announcing the harvesting of the last neck of corn; drinking and a harvest supper, hosted by the farmer, followed.

Harvesting was the high point of the farming year, but there were always mundane jobs like ploughing, sowing, weeding, and tending to the animals. Great grandmother, Grace, would have done a lot of this rural labour, besides looking after the children. Girls were tasked to help the farmer’s wife—farm work like bringing in the fuel, feeding the pigs, boiling the potatoes, weeding corn, picking stones, winnowing and household work like making bread, mending stockings, washing and carding wool. Young boys were in charge of driving the oxen for ploughing and drawing carts and wagons.

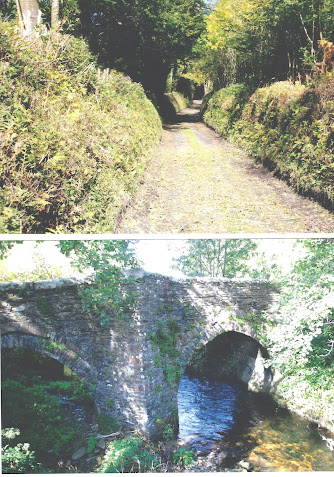

Until the 1850s, John and his family lived and worked on Barley Splatt farm; around 1858, (now aged 69) he went to work at Bofindle farm. Both these farms lie just down the hill from Warleggan village.

Barley Splatt farm--John, an agricultural labourer and his second wife, Jane, were living here in 1851 in a humble cottage

Bofindle farm--John & Jane lived and worked here from abt 1858 until his death

John would have lived in a small outlying stone cottage. “Most cottages were one room—built on any level of waste land. Walls were of rammed clay or turf and floors were beaten earth.” Possibly it had a thatched roof. Likely there were 2 bedrooms—one for the parents and the youngest children and one for everyone else. Close outdoors would be the privy and animal enclosures—health hazards for all. By the mid 1800s, John’s house would likely have had the basics like table, chairs, beds and bedding, plates, cutlery and maybe wine glasses, a mirror, maybe a watch or clock and a chest of drawers rather than a basic clothes box. But in a period of unemployment, illness or hardship, the only option would be to sell off these household items.

There were three staples in the Cornishman’s diet—barley,

bread, potatoes. As the Lemin family lived miles from the sea, it is uncertain

if they would have often eaten pilchards (small herring-like fish) chopped up with

raw onions, salt, diluted with cold water, eaten with fingers and accompanied

by barley or oaten cakes. (it is said that cottagers stored 1000 pilchards each

winter. Where would they have put them in their small cottages?) And perhaps

the Lemin family grew cabbages, onions, carrots, and turnips to add variety to their

diet. The simple Cornish diet resulted in a stunted growth; the median height of a Cornishman was five foot six. Damp houses, insufficient clothing and rudimentary

sanitation exposed people to disease. Every year, thousands, especially young children,

died from typhoid, typhus, dysentery, measles, whooping cough and scarlet fever.

Ironically due to the

hard exercise, fresh air and humdrum diet, rural workers were the healthiest

people in England. At that time the average life expectancy in England was 41

years. John died on Sept. 15, 1861 (aged 76) in his cottage on the Bofindle

Farm. He is buried alongside his parents and wife Grace in the St.Batholomew’s

Churchyard.

.

Son: John Lemin (1809-1861) In March 1831, at age 22, perhaps for the adventure, John enlisted in the English army—the 73rd Regiment of Foot. To enlist he was paid a bounty of 2 shillings. He had to swear an oath of allegiance and that he understood the articles of service. John was illiterate and signed with his mark. He was first stationed in the Mediterranean (Malta, Ionian Islands, Gibraltor) for 4 years, then 3 years in North America (Nova Scotia and Canada during the Rebellions) and the rest of the time in England. Twice he was imprisoned for a month for some identified infraction. John served in the British army for 13 years, 7 months. He was discharged in October 1844 as medically unfit for service. (lung problems brought on by damp and cold of the ships.) John returned home to Cornwall. He never married and for a few years worked as an agricultural labourer. Eventually he lived off his army pension as an out-Chelsea pensioner. John died in 1861.

John Lemin--signed with his mark as he unable to read or writeSon: Like his father, William (1811-1903) was an agricultural labourer from age 13 until he “retired” around age 80. William and his wife, Martha had seven children. In 1861, four of these children were working in the tin mines. In an interview, William said his family had to live on 9 shillings a week but that his wants were few and he “did not smoke.” His father taught him his prayers on Sunday evening. A little money was earned through bee-keeping. Food was pasties, pies or a boiling stew. Very little beef was seen and the farmers did not kill their pig until they weighed between 300 and 350 pounds. Shortly before he passed, William was excited to attend his first circus. William died in the St. Austell Workhouse. William claimed that he was over 100 years old (but it seems he might have exaggerated that.) William could not read or write.

Son: Richard (1813-1856) worked in copper mines; married Ann Oliver

Son: Charles.(1821-)..info unknown

Daughter: Jane Oliver Lemin (1816-1896) (my great-great

grandmother) Jane may have met Richard

Harper at a market day. He was a widower and described as “a powerful young man

weighing about 200 pounds and full of energy and determination to push aside

every obstacle.” They married in the Warleggan Church in August 1838, lived in

nearby Temple where Richard was a tinner. Four of their ten children were born

in England before the family decided, in 1847, to emigrate to Canada. The

family settled in Pilkington Township, Wellington County where he cleared his bushland

and built a farmhouse. Richard was a successful

farmer for 50 years, tax collector and a local councillor. Jane died on the

farm in 1896 and Richard died the next year. They are buried in the Elora

Cemetery.

Jane's signature on her will

Elora Cemetery

Daughter: Elizabeth (1818-1890) Elizabeth married Cornelius Cook (1808-1895) in Warleggan on Boxing Day 1844. They had four children. Cornelius sometimes worked as an agricultural labourer and at other times in the Bodmin copper mines. His sons and daughter also worked in the mines. It was after their daughter Elizabeth Hussun immigrated to Canada in 1870 and son John to Boston in 1885 that Cornelius and Elizabeth also decided to emigrate. They lived with their daughter’s family on their farm in Puslinch Township, Wellington Co. Elizabeth died Oct 1890 (age 71); Cornelius died 1896 (aged 86). Both are buried in the Guelph Woodlawn Cemetery.

Woodlawn Cemetery, Guelph

Comments

Post a Comment