#41 DIED AT VIMY

THEODORE ST.CLAIR McDONALD

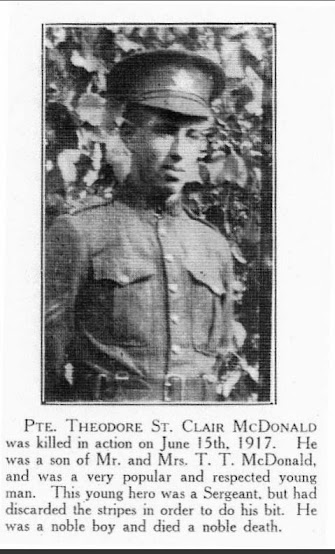

Theodore St.Clair McDonald was born in Wingham on January

19, 1898. His parents were Thomas McDonald, a local barber, and Mary Jane

Homuth.

Wingham Advance May 18, 1916

Theo was apprenticing as a drug clerk when he enlisted with the 161st (Huron) Battalion. Who knows for what emotional or political or social reason he enlisted on November 30 1915.

Exeter Advocate June 29, 1916

As the war progressed and casualties mounted on the Western Front, it was necessary to replace losses in the field with fresh troops. New battalions trained in Canada were sent to England where most were absorbed into reserve battalions; thus, the 161st was absorbed into other battalions. Theo was among the 150 men and 7 officers who were transferred from the 161st Huron Battalion to the 58th Battalion. They left for France on November 29, 1916.

There is an excellent book by Kevin R.Shackleton, Second

to None The Fighting 58th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary

Force that details, by month and day, where the battalion was and in what

military actions it was engaged. (chapter headings below are from this book.) While

Theodore McDonald is not mentioned, it’s fairly certain this book outlines what

he saw and what he was doing alongside his fellow soldiers when he was in

France from December to June.

December 1916. Anatomy of a Trench Raid. The 58th battalion was located part way up Vimy Ridge. In December, the battalion focused on the timing and method of their raiding parties. The raids were well-organized with each group assigned specific roles—e.g. one party would detonate an explosive on the enemy wire so another party could quickly go through the gap; another party would carry a portable bridge to place over the enemy trench so they could get to the enemy’s communication trench. Artillery and mortar crews practised firing their weapons to hit a specific target. The goal of the raiding parties was to take enemy prisoners, inflict casualties and damage enemy trenches. Theo’s battalion spent Christmas 1916 in the trenches in France. “Christmas Day was clear and bright, with a light wind from the southwest. The men carried out their fatigues before receiving a Christmas dinner of extra rations, particularly of rum and a special issue of pudding. There was no fraternizing with the enemy as had happened in the first two years of the war.” The battalion remained in brigade reserve until December 30, when they were returned to the front line.

January 1917. Winter Sets In. Theo was on the front

line on New Years’ Day, 1917. “The trenches were in terrible disrepair; many of

the dugouts in their section of the line had caved in as a result of the

prolonged wet weather and steady German shelling.” The men dodged enemy mortars

and some suffered shell shock. The battalion then served as a reserve brigade

which meant positioning away from the front line. During the next five days, it

suffered little from enemy activity. “The men spent the first day on bath parade,

cleaning up from the mud of the front-line trenches. The next day was Sunday,

and there was a church parade followed by an inspection. The remainder of the

day was a holiday, possibly in recognition of New Years. The area around Arras

likely provided diversion for Theo and his comrades and they may have visited

small shops and cafes. Men with money to spend would always find a welcome in

any inhabited town or village. Canadians learned enough French to ask for basic

items. In the larger centres, the men could have their photos taken and made

into postcards to send home. There were many Canadian units in the area, and the men often took

time to walk to neighbouring units to visit friends or relatives.” Training now

focused on learning about the key weapons and elements of trench warfare.

February 1917. Preparation for Something Big. By now,

airplanes were being used to photograph enemy lines, drop bombs, strafe the

enemy with machine guns and scout out and relay information about enemy

positions and activity. The 58th was introduced to a new platoon drill

where two platoons would lead the attack and another would come up behind in

support or reserve; this was called a creeping barrage. All this training was in preparation for

“something big.” But there were also the usual church parades and inspections,

and route marches were used to keep men fit. Inter-unit football games fostered

morale and gave men an outlet for their aggressive energies... “the period away

from the front was being used to restore the spirits of the men, they had time

to go for meals of eggs and chips at local cafes, wander though the villages,

take in the latest Charlie Chaplin film and make the close acquaintance of the

French girls.”

March 1917. Keeping the Enemy Off Balance. There was a lot of training on close-quarter fighting in trenches using bayonet and rifle. Gas respirators were tested with non-lethal gas. There were trench raids; it was British policy that each division conduct two raids a week. Mid March, the regiment was sent to the front line.

April 1917. The Battle for Vimy Ridge. The 58th was to be a reserve battalion for the assault on Vimy Ridge. The Germans had held this six-kilometre-long ridge of high ground for over two years, and it was said to be the most heavily fortified portion of their front. The area behind the Canadian front lines was busy “as roads were prepared for the movement of vast quantities of stores and munitions necessary for the attack. Trenches and tunnels were dug to allow the men to move, unmolested by enemy fire, to the point where they would launch their attack. Telephone cable was buried to keep it safe from enemy shelling.”

The 58th Battalion was

heavily involved in these preparations and many of the men were assigned to

working parties. The wet weather meant that the roads and trenches were very

muddy, making the work difficult, but the 58th’s morale was still

high. Bombardment of the enemy positions increased. It was important to locate

and silence German artillery batteries. One way was through aerial photographs

to locate enemy digging or repositioning. Another method to detect the enemy

was to have observers equipped with high-quality surveying instruments plot

muzzle flashes of enemy artillery when fired. Lastly the Canadians developed a

system of sound ranging that used a series of microphones to record the sound

of guns firing, again to locate the enemy batteries. All these methods were

combined to locate and knock out, as many enemy batteries as possible before

the Canadian infantry went over the top.

The 58th discontinued its working parties and on April 9, moved up to the assembly trench. At 5 am, the final bombardment began; the British had allocated 2.6 million shells for this bombardment and the new shells detonated on impact in the enemy wire (rather than under it) so that obstacles could be better cleared. Most of Theo's 58th battalion was in reserve until April 11; the platoons had difficulty capturing enemy trenches as German snipers caused many casualties. On April 12, when the Germans began a withdrawal from the area, the 58th was ordered to move forward and take the trenches. “The men were beginning to show signs of strain from being on the move and in action for an extended period…on April 15, the unit moved further east to take a position on the railway line. The newly captured territory yielded a substantial haul of booty…ammunition and engineers’ stores, 8 artillery pieces, one trench mortar…the enemy dugouts had electric lighting, something unheard of in the Allied front line trenches.” After nine days, now reaching the end of their endurance in the line, the 58th was relieved and sent back to billets. In April, the 58th had 23 men killed, 81 injured, 1 gassed, 11 missing.

Vimy landscape today showing the bomb craters

May 1917. Keeping the Pressure On. The month began

with the unit in reserve position on Vimy Ridge, occupied with working and

salvage parties on the Ridge. In mid-May, the unit sent men out to various

working parties for road repair and trench cleanup. The front was still active,

but the men knew how to stay out of harm’s way and the casualties were light. A

new occupation was assisting the Canadian engineers in tunneling operations;

the tunnels carved out of the chalk was significant to success at Vimy as they

allowed men to assemble safe from enemy artillery fire.

June 1917. Leading the Way. The battalion started the

month of June in reserve. From there then men were sent out on working parties.

The company trained, went to church. The War Diary describes June 14 as “quiet,

with normal aircraft activity. Enemy rifle fire was active during the early

morning and patrols were out but no encounters with the enemy. Enemy trench

mortars bombarded the position that night.” Enemy snipers claimed the life of one man who

was most likely Theodore. “The casualty bill was heavier on Friday June 15 with

three more soldiers killed and five wounded. They may have been hit as they worked

at improving the battalion’s trenches or by the trench mortar attack that

evening.”

he Battle of Vimy Ridge proved to be a great success but it came at a heavy cost. Of the 100,000 Canadian who served there, more than 10,600 were casualties and 3,600 who died. Private McDonald was 19 years, 5 months old when he was killed.

Theodore St.Clair McDonald is buried in Petit-Vimy British Cemetery, near the little village of Vimy. On his grave it reads, “Be Thou Faithful unto Death and I will Give You a Crown of Life.” This cemetery contains 94 First World War I burials, 23 of them unidentified.

Theodore also has a memorial stone in the Wingham Cemetery.

Wingham Cemetery

He is remembered on the Wingham cenotaph and in Ottawa in the Book of

Remembrance.

THEODORE ST.CLAIR McDONALD

b.

Jan. 19, 1898 in Wingham, Huron Co.

d.

June 15, 1917 in France

my 2nd cousin 1x removed (Homuth line)

of note:

Theodore died in June 1917. In November 1917, there was

an article in the Wingham newspaper about Theo’s grandfather, William Homuth.

Wingham Advance-Times Nov. 22, 1917.

WILLIAM (WILHELM) FRIEDRICH HOMUTH

b.

Oct 26, 1838 in Brettenstein, Prussia, Germany

m. Elizabeth

Gingrich (1850-1902) in 1871?

d.

Apr. 20, 1928 in Toronto

So sad, all the young lives wasted. vs

ReplyDeleteI wish these sad events in history never happened but they keep on recurring…..very sad.

DeleteYour writing certainly keeps us interested and wanting to read more.

ReplyDelete