#22 CLAIMING A MEDAL

CHARLES LEMIN HARPER (1843-1910)

I taught

Canadian history for many years and one important lesson was the causes of

Confederation. One was Canada’s fear of a full-scale American invasion by

the victorious Union army after the US Civil War. I also always discussed the

Fenian Raids. Little did I know then that I had a great-great uncle involved in the defence of the colony against the Fenian threat. Canadians

realized that if a ragtag band of Irish-Americans could pose a potential

military threat, then an even bigger danger was the US army and the US belief

in Manifest Destiny. Confederation would, it was expected, give greater

military protection to the British American colonies.

Even before the American Civil War, Irish-American nationalists had formed the Fenian Brotherhood with dreams of attacking Canada. (The term, Fenian, comes from the Irish-Gaelic term Fianna Eiriann, a band of mythological warriors.) After the US Civil War ended in April 1865, the Fenian Brotherhood proposed to mobilize hardened and unemployed Civil War Veterans, seize Canada, and hold it hostage to trade back to Queen Victoria for an independent Ireland. Fenians also believed that when Britain deployed thousands of troops to get Canada back/fight the US, British troops in Ireland would be reduced to the level that a successful uprising by the people of Ireland could actually take place.

A Fenian government for Canada was established by a group in New York City, bonds were sold to be repaid by “The Irish Republic”, and military regiments and brigades were formed.

The Fenian Brotherhood argued that Canadians, especially the 175,000 Irish Catholics resettled during the Great Famine, would welcome them as liberators. “Canada would serve as an excellent base of operations against the enemy [sic England] and its acquisition did not seem too great an undertaking”, wrote the Irish nationalist architect of the Fenian Raids. Indeed, while the number of sworn Canadian Fenians was small, they were a pervasive presence throughout Irish Catholic Canada. There were Fenian circles in all major urban areas and in towns such as Guelph, which one newspaper described as “the central point for Fenian operations in Ontario”. Support came from all economic groups-- artisans, skilled and semi-skilled and unskilled workers, small manufacturers, merchants and professionals; there were Fenians in rural townships like Puslinch [Walsh homestead] and nearby Aberfoyle was described as “Little Ireland”. Support for Fenians heightened the Irish Protestant-Catholic tensions in the area. While it was unlikely boasting that 100,000 men were ready to rise against the Canadian government during the winter of 1865-66, there were, however, “secret service corps” that would “cut the telegraph lines, destroy the railway bridge that connected Canada West and Canada East, infiltrate the Canadian militia, bribe British soldiers, and burn down government buildings”.

Fenian rhetoric was met by an equally impassioned Anglo defiance, especially by the Orange Lodge.

The Elora Volunteer Rifle Company

Charles (1843-1910) was a young boy when he immigrated in 1849 from Cornwall, England with his parents, Richard Harper (1815-1897) and Jane Oliver (Lemin) Harper and 3 siblings. The family settled in Pilkington Township, Wellington County, a few miles southwest of Elora. In the early 1860s, Charles joined the Elora Volunteer Rifle Company. (It is possible that his father Richard also joined for a short while.)

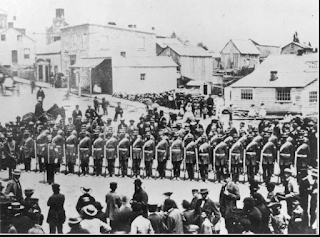

The Elora Rifles in full uniform, May24, 1862The Elora Volunteer Rifle Company was organized July 30, 1861 in response to the outbreak of the Civil War in the US, and in anticipation that war with the US was imminent. “…considering the unsettled state of affairs in neighboring Republic, it is highly desirable that a Volunteer Rifle Company be organized in Elora.” And there was a growing fear of an invasion by the Irish-American Fenians.

The Elora Company drilled for the first time in August 1861 and continued regular drills sans uniforms and rifles over the winter. Rifles and overcoats were received in April 1862. The remainder of the uniform was purchased by the members for about $20 and was made by local tailors. The government specified green for riflemens’ uniforms, but the Elora Company experimented with various fabrics; they placed men at various distances and covered with various samples of cloth and then selected a dark fawn fabric made in Galt as they felt this colour was less likely to be seen by the enemy. The officers and men were paying for their own uniforms so insisted on choosing the colour. That is why the Elora Rifle Company was the first in Canada to wear the colour that has been found the most serviceable and anticipated by many years the use of what is now called the “Khaki” uniform. The Elora Company was given permission to wear the khaki uniform on Sept 27, 1861.

The Elora

Volunteer Company first paraded in full uniform on May 24, 1862. They marched

to Salem and back accompanied by the Fire Company and the Elora Brass Band. They

continued drilling from 1862 through to 1865. Officers from British regiments

were sent to Canada to provide training. In February 1864, Charles Clarke[i]

of Elora assumed command of the Company. During the latter stages and following

the end of the Civil War, there were many rumours of a Fenian invasion of

Canada. Captain Clarke had his men drill 74 times in 1864 to ensure their

readiness.

Fenian

Raids

In March 1866, Fenians were massing along the Canadian frontier and planning a 3-prong attack at Fort Erie, Prescott, and the Eastern Townships. Ten thousand Canadian volunteers were called up.

Government call for volunteersThe telegram was received on Saturday Mar 31 1866 to have 55 members of the Elora Company in readiness for active service and orders were received the following Tuesday to march to Chatham. Captain Clarke’s most difficult task was to reduce his Company to the requested 55. Charles was included in that selected group; as a private, he was paid 25 cents a day. (the Lieut. Colonel received $4.80)

Elora Rifles, April 2 1866 before departing for duty...Charles must be in this photo somewhere

On Monday, April 2, the Company assembled upon the ice on the river and had their photograph taken. That evening, the Elora Branch Bible Society presented each soldier with a Bible. The Company then drilled in front of a large crowd (many young women in attendance!) They departed Elora on Wednesday, April 4 at 5 am. They drove to Guelph in wagons, arrived at 8:40, marched to Lindsay’s Hotel for a breakfast provided by the Guelph Town Council, marched to the Grand Trunk Station and caught the train to Chatham. On their way to Guelph, they passed through deep rifts of snow but in Chatham they found summer weather with dust blowing on the streets. In Chatham, the Company drilled for 6 hours daily. No Fenian invasion happened. After six weeks, they received orders to return to Elora. In Guelph, the Company was met by friends and the Brass Band; they were paraded through the streets and en route to Elora they were feted at 2 different hotels. The Company finally reached Elora after midnight, were greeted by a huge bonfire, cannon blasts and many loud cheers, then attended another banquet. They paraded through the village again the next day and attended a reception “to which all in Volunteer Uniform, with their partners, should be invited.” The men returned to their jobs and farms.

The Company was again called out Saturday, June 2. The telegram was received just after 8 am. Within the hour, the Company had assembled and was in Guelph by noon. In Guelph, the men learned that the telegram to the Elora Company had been delayed by twelve hours and this prevented the company from participating in the Battle of Ridgeway; it is quite possible that this telegram had been intentionally undermined by enemy forces. “The delay in transmitting this important telegram was never satisfactorily explained, and the men, who had drilled diligently to prepare for such an emergency, ever afterwards regretted that through this delay they had been prevented from taking part in the Battle of Ridgeway, which was fought that day.”

The Battle of Ridgeway, near Fort

Erie and across the Niagara River from Buffalo, was fought on June 2, 866

between 600-700 Fenians and 850 Canadian troops. The inexperienced Canadians,

short on food, maps and ammunition, were routed before the Fenians retreated,

in haste, to the US—some on logs, rafts or swimming. The Canadians loss was 9

killed, 37 wounded (some severely enough to require amputation) and 22 later

died of wounds or disease; the Fenian loss was 2 killed and 8 wounded. On June

6, President Andrew Johnson reacted by issuing a “Neutrality Proclamation”

ending Fenian hopes for official support from the US government. The Battle of

Ridgeway was Canada’s first modern battle, the first fought exclusively by

Canadian troops and led on the battlefield entirely by Canadian officers, and

the last battle fought in Ontario against a foreign invasion; the battlefield

was designated a National Historic Site in 1921.

Having missed the Battle of Ridgeway, the Elora Rifles were instead sent to Port Edward, near Sarnia. The trip proved uneventful, but when they arrived in Sarnia, they found that no one had given much thought to feeding or housing the hundreds of soldiers; fortunately, the weather was warm. Tents soon arrived and military authorities achieved a measure of organization. On Sunday, the Elora Company attended church, but fearing an enemy invasion, each man brought sixty rounds of ammunition with him to church. A major problem was the lack of reliable information as no one knew the size of the Fenian force assembling in Michigan, or even if there actually was one. The Elora patrols saw no threats of consequence—only some suspicious signaling on the lake that quickly ceased, and a cargo ship flying the green Fenian flag. Soon units of the US Army arrived in Port Huron, to discourage any assembly of Fenians and prevent any border incidents. To dispel tensions, General Sherman of the US army visited the Canadian troops and chatted with the soldiers, including the Elora Rifles.

The Elora

Company was sent home after a month and they were enthusiastically welcomed

home; a “day was set apart by the inhabitants of Elora and surrounding

country, as a public holiday, for the purpose of holding a great welcome home

picnic to our gallant volunteers…This will be the greatest popular

demonstration which Elora has ever seen.” Sandwiches, cake, speeches, band

music and presentations were the order of the day.

The events of 1866 firmly entrenched the volunteer militia into the fabric of the Elora community. Each summer for half a century, men turned out for a week-long training camp. For many of the men, this was an annual vacation, a chance to get away from work and family for a few days. Sometimes there would be problems with employers who did not care to have key workers away each summer. Another feature of the Elora militia was the annual ball which became the major event of the social season. The first Elora ball took place in February 1866. Officers, out-of-town guests and prominent local people attended and danced to the Quadrille Band; the assembly sat down at midnight for supper and the festivities continued to 6 am. But these balls were really snob events. Rarely did more than a half dozen of the enlisted men, like Charles Harper, attend. A commission in the volunteer militia became a desirable asset; soon Ontario rivalled Kentucky in its profusion of militia colonels.

Significance

Through the winter of 1867 there were rumours of more planned Fenian raids. Alarm declined through 1867, but rose again in April 1868 when D’Arcy McGee (Father of Confederation, Member of Parliament, Irish-Catholic, and a vehement objector to secret paramilitary societies trying to tear apart the very country he had just helped create) was assassinated on Sparks Street, Ottawa. A group of Fenians was rounded up and in February 1869 Patrick Whelan (no relation that I can tell) was publicly hanged for the killing. Whelan’s last words were “God save Ireland and God bless my Soul.” In 1870, a Fenian Raid into Quebec was forced back.

Aside from

the plan being ridiculous from the get-go, the Fenians suffered from poor

leadership and a lack of support from both sides of the border. They were broadly (and incorrectly) seen by

the public and press as a radical Catholic terrorist group. But there was a lot of

antagonism towards Irish Canadians as many thought they condoned and supported

the Fenians; some even speculated that the Fenians were part of a secret

conspiracy by the Pope. As a result, thousands came out against the Fenians.

Also the Fenians had overestimated the influence of Irish interests in US

politics. The US had just finished fighting a Civil War and the last thing the

country needed was a war against Great Britain. After the failed invasions, the

Fenian Brotherhood fell apart.

The Fenian

Raids of 1866 and 1870, McGee’s assassination, and a 1869 terrorist sabotage of

the Welland Canal have been categorized by historians as a comic-opera

adventure; nonetheless they helped unite the new country and fed a fear of

American annexation. Some Irish Catholics left Canada for the United States.

The Orange Order in Canada acquired bragging rights as a national defender.(2)

But what about Charles?

For a while, Charles blacksmithed in Elora. He married Ann Burkholder and they had two children. He farmed in Pilkington and Woolwich Townships before moving back to Elora. It wasn’t until 1899, when Charles was 56 years old, that the Canadian government finally recognized the volunteers who had defended against the Fenian Raids. Charles received a Canadian General Service Medal. This medal is a silver circular medal with Queen Victoria wearing the Order of the Garter and contains the phrase “Victoria Regina et Imperatrix”. On the reverse is the red ensign of Canada surrounded by a wreath of maple leaves surmounted by the word “Canada”. Each medal has the recipient’s name, rank and unit engraved on the rim. (How I wish I had possession of this medal!) Only the veteran could apply for the medal and it was awarded only if he could document that he had been on active service, or had served as guard where an enemy attack was expected (this was how Charles qualified). A total of 16,668 medals were awarded.

In 1901, Ontario passed legislation authorizing land grants to individuals who had served in the militia during the Fenian Raids. Applicants who submitted proof of service received a location ticket for a 160 acre lot in Northern Ontario. Charles must have declined the land grant.

One wonders why it took the government so long to recognize these veterans. The answer is simply political. John A Macdonald was serving as Minister of Militia in 1866 and as telegrams poured in with updates of rebel advances, Macdonald was too drunk to read them. Either he had gone a bender and coincidentally the Fenians chose one of these moments to invade, or John A freaked out and then took to the bottle. The militia officers were politically-connected, ambitious, upper-crust, social-climbing gentlemen, amateurs—wealthy merchants, attorneys, railway builders, professors, landlords, civil servants, politicians, and entrepreneurs who saw their military service partly as a route for social advancement, and partly as a function of their class to “lead the lower orders forward in their duty to Queen and Empire"; (Three boys from the University of Toronto Rifle Company were killed at Ridgeway while their professor officers, who had founded the company and drilled them, remained home when called out for combat, claiming that “academic duties” kept them in Toronto.)

Ridgeway was an embarrassment

and politicians preferred to blame the defeat on the cowardice and incompetence

of the rank-and-file soldiers while exonerating the officers who were socially

prominent and had been appointed by Macdonald’s government. It is interesting to note that medals were finally awarded in 1899, years after Macdonald died in 1891.

Charles Harper died on December 5, 1910 in Elora and is buried in the

Elora Cemetery. “He was a consistent member of the Elora Methodist Church, a

quiet, kindly man respected by all who knew him.”

Sources

Stephen

Thorning’s “Valuing Our History”. The Fergus-Elora News Express,

March 25 1998, April 8 1998, and Wellington Advertiser June 19, 2009.

History of

Elora

Donald V. Macdougall

“Henry’s Sword and The Fenian Raids” in Families Quarterly Publication of the

Ontario Genealogical Society. Vol 62. No 2. May 2023.

“Elora Rifle

Company 1862” Track and Traces. Newsletter of the Wellington Co Branch

OGS. V.4. No.2. Spring 2004.

Peter

Vronsky “Battle of Limestone Ridge Canada’s First Casualties”. Toronto Star.

Nov. 11, 2009.

[i] From The Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Charles Clarke (1826-1909) served as Liberal MLA for Wellington from 1871 to 1891 and was Speaker of the Ontario Legislature from 1830-1883. He was born in Lincoln England, came to Canada in 1844, became editor of 2 Hamilton newspapers, opened a general store in Elora and established the Elora Backwoodsman paper. He served on Elora council, and as reeve. In 1874, he helped introduce legislation that established secret ballots in the province. He was clerk of the legislature from 1892 to 1907. He died in Elora in 1909. Before his death, he published Sixty Years in Upper Canada which is valuable for his recollections of Ontario politics. His interests

and outlook exemplified those of the educated, liberal, middle class Victorians. He advocated temperance and agricultural improvement, he promoted horticulture, ornithology and natural history as civilizing pursuits that countered the materialism of the age and advanced “the general intelligence of our people.” He commanded the Elora militia during the Fenian Raids and was promoted to a lieutenant-colonel of the 30th (Wellington) Battalion of Rifles. Familiarly known as Colonel Clarke, he became something of a sage in his private and public life. "The sage", he wrote, "must teach, the young must act."

2.

I learn so much from your stories.

ReplyDeleteSuch an interesting account of this chapter in Canadian history!

ReplyDelete