#7 COUSINS IN THE GILDED AGE...AND A LOT OF TRIVIA

MY BLAZO COUSINS

One of my recent favourite miniseries is HBO's The Gilded Age, a

drama about life in New York City at the end of the 19th century, an

age of “immense economic change, great conflict between the old ways and new

systems, and a time when huge fortunes were quickly made and lost.” The rapid expansion of industrialization led

to real wage growth; the average wage per industrial worker rose from $380 in

1880 to $564 in 1890, a gain of 48%. But the Gilded Age was also a time of

abject poverty as millions of immigrants poured into the United States and the

inequality between the rich and poor was glaring and contentious. From 1860 to

1900, the wealthiest 1% Americans owned 51% of all property, while the bottom

44% of the population claimed just 1.1%. The wealthy tycoons spent their money

on extravagant mansions, travel, lavish parties, and luxuries. “If you have it,

flaunt it” and these robber barons/captains of industry wanted everyone to see their

wealth and status.

A. The Blazos

William Augustus (W.A.) Blazo was born in 1829 in Maine; he

married Mary Elizabeth Farnum in Milton, Mass. in 1858. They had 3 sons and

four daughters. Oldest son, William Greenleaf Blazo, became a Boston police

officer; youngest daughter, Hattie, married American artist Julius Rolshoven;

Lillian married Robert Lincoln Lippitt, one of the world’s first road-racing

cyclists. (Robert’s father was Governor of Rhode Island, one brother also

Governor and another brother elected to the US Senate.) But it was son Summer

Augustus William (A.W.) Blazo who joined his father in business and on the New York social scene.

B. BUSINESS

Both father (W.A.) and son (A.W.) had early training as carpenters before starting to buy properties for housing development on the Boston outskirts. In the 1880s, they moved to 58 Decatur St, Brooklyn, New York City.

58 Decatur St., BrooklynTheir company sold all manner of construction materials. They also bid on construction contracts in New York. In 1888, A.W. got the mason contract for the Amphion Academy, home of the Brooklyn opera and a place “not a whit inferior to the very handsomest of New York theatres.”

The Amphion Theatre had a seating capacity of 600 and was a major theatre in the 19th century. An interesting story happened in December 1910. It was the last act of the play with a ranch scene when a wolf was brought on stage confined in a ten foot barbed-wire cage. The wolf worked its way out of the cage, jumped into the orchestra and sprang on the nearest person--a woman "screaming in fear who struck at the animal with her muff. The wolf's jaw snapped shut, closing about the woman's hand, and as she dropped fainting into a seat, the wolf turned and sprang onto another." Terrified people who had crowded the aisles trying to escape prevented the keeper from reaching the wolf which then snapped and bit the ankles of six others and the hand of a policeman until it was subdued, bag over its head and safely removed. Not everyone had been able to get out of the theatre and after the animal had been caught and the victims' injuries attended, the curtain which had been lowered, was raised again, and the last act completed. The wolf did not appear on stage again." The Amphion started to fall on hard times, became more of a Yiddish Vaudeville and then a cinema. In one story when a female lead failed to show up for a performance, the manager cancelled the show and refused to pay the troupe; they promptly beat him up. (don't need an address to deduce that was Hell's Kitchen, Brooklyn.) By the 1930s, the Amphion was running silent movies. At that time, the man who played the piano was fired for playing songs that were "inappropriate". The management ran a weekly giveaway; it was possible to acquire a complete set of china, one plate at a time. The theatre was shuttered for at least ten years before being demolished in 1940 by the NYC Housing Authority as part of a slum-clearing project.

Sometimes the Blazos got caught up by political intrigues. For instance, in 1889, A.W. twice submitted bids for the Republican Union League Club; both bids were the lowest, yet rejected, and then he lost on the third bid. His friends felt that the bids had been leaked to give his competitor an advantage. To A.W.’s credit, he accepted his loss with style and said, “I wish to distinctly state that I am not going to make any complaint…the gentlemen comprising the committee are my friends. There was nothing crooked about the way this contract was awarded.”

In 1900, A.W. sought a patent for his “plaster-regulatory plate”, a way to improve and strengthen partitions and walls by layering plaster binding on wall blocks, which could bind the blocks with/without the use of cement or mortar.

New York Times Nov 1899In the 1880s, A.W. became one of the proprietors of the new Coney Island Roller Skating Rink.

Roller skating was just starting to become popular; it was marketed as an appropriate activity for men and women to do together, allowing young couples to meet without reprisal or chaperones. In 1885, Joseph Cohen, a father and unemployed, entered a roller skating contest at Madison Square Gardens. He hoped to win $50 offered to all who skated for six days. Days, not mileage, mattered. Joseph skated 548 miles over the six days but fell sick and died from “brain exhaustion produced by the excitement and fatigue of the match.” This Inquest garnered a lot of newspaper attention. The Coroner said, “I intend …to discover whether roller skating is healthful or injurious. It is a question of serious importance to every father whose children frequent the roller rink.” The jury recommended that no contest be allowed that kept contestants on the floor for more than 4 consecutive hours. To his credit A.W. Blazo was one of the few invited roller rink managers to attend the inquest; using good business smarts, he presented all present with admission tickets to his rink, and invited them to make a trial of roller skating.

C. SOCIAL

Just as business in the Gilded Age was ruthless and

competitive, so was New York Society. The Four Hundred was the number of

fashionable and socially acceptable people in New York who could fit into Mrs.

Astor’s ballroom. Her list of the crème de la crème consisted of bankers,

lawyers, brokers, real estate men and railroaders; it included a mix of “Nobs”

and “Swells”. Nobs came from old money, (like the Astors) and the Swells were

drawn from the nouveau riche (like the Vanderbilts) whom Mrs. Astor felt,

begrudgingly, were able to partake in polite society. New York society was

notoriously closed to newcomers, who were trying to spend their way into

society.

The Blazos rubbed shoulders with some of the Swells. It was up

to the Blazo women to give the family visibility at city social and charity

events. In the early 1890s, Mary

Elizabeth and her daughters devoted their time to fundraising for the Brooklyn Memorial,

a hospital for sick women and children. The new hospital was to be a “modest,

plain but well-built structure, perfectly ventilated, warm, sanitary, with a

clean and convenient kitchen and laundry, and a thoroughly equipped surgical

unit.” It was staffed by female doctors and was a training school for nurses.

Mary Elizabeth was a standing member of the Executive Committee and

the Housing and Purchasing Committee.

And she was a key member of the fundraiser’s Committee of Arrangement

which meant she played a major role in deciding who ran the various charity

tables. The many, many tables included

candy, apron and utility, cake, flower, mystery, gipsy (palmistry and

fortune-telling). An interesting table

in 1891 was the “curio table” which showcased everything from “Hottentots to

mound builders.” Curios there included items such as an Indian Tomahawk, finger

cymbals for dancing girls of the Nile Valley, a stamp box from Cairo, face

veils and clogs from Damascus, a figure from an Egyptian mummy case, slippers

from Constantinople, a piece of Captain Cook’s ship, and necklace of a native

princess of the South Seas Islands.)

Mary Elizabeth and her daughters, Hattie and Lillian, were

assigned to run the popular Lemonade Well. Alice and Hattie “dressed alike in

organza colored silk, hair of both heavily powdered. The white hair youthful

features furnished a contrast that was very pretty and which importantly

attracted a great many thirsty visitors.”

The Blazo women also were in charge of the Dolls and Toy Table. The doll

exhibit had dolls of every size and description, but the biggest draw was one

donated by Mrs. George Gould, daughter-in-law of railroad magnate, Jay

Gould. This doll was as tall as a 5 year

old child, and was dressed in the clothing of Mrs. Gould’s first-born. “This

consists of a modern and costly pattern and a exquisite bonnet, made of ostrich

tips and silk.” Another 15 pound doll had solid gold rings on its fingers.

Another doll was a Jennie Lind heirloom doll.

The fundraisers ended in set dances—waltz, lancers, Yorke,

gallop, quadrille, schottische, polka, caprice.

Another fundraising effort was a Minstrel Show. The newspaper item read: SOCIETY WOMEN AS MINSTRELS...They will "Black Up" and Give a Performance in Brooklyn. The women connected with the Memorial Hospital for Women and Children in Brooklyn are getting up a minstrel show at the Academy of Music. All the performers are to be society women. They will "black up" in the most approved minstrel style and crack minstrel jokes, sing minstrel songs, and play minstrel banjos and tambourines, just like real minstrels. It seems likely that Mary and perhaps her daughters and daughter-in-law also participated in this show.

Daughter-in-law. Alice Blazo may, or may not, have been close friends with many society women; the Blazos had, after all, only lived in the city for a decade. What is known, however, is that Alice had one longtime intimate friendship with Helen Parrott. Helen moved from Boston to New York City in 1883; she had no immediate relatives and had educated and supported herself from childhood. Helen got a job as a clerk in one of the city’s largest dry goods stores and as the head clerk of the cloak department “she gave entire satisfaction and won the confidence and esteem of her employers. She was described as “a comely woman of business-like ways and an even manner. She was entertaining and never allowed her temper to gain the ascendency.” Helen was engaged to Louis McCarty who was the head night operator of the Associated Press. Soon after, Louis discovered he had consumption and was told to go to the pine woods of North Carolina. When this treatment did not help, he was advised to go to Colorado. The wedding was postponed and as his savings had been used up on the first trip, Helen paid the expenses of the Colorado trip. Nonetheless Louis died, Helen became very despondent and quit her job. She wandered into New York City and walked into the North River. It was Alice who went to the morgue to identify her friend’s body and only Alice, her husband A.W. and her Blazo in-laws attended Helen’s funeral.

D. GREYLOCK VILLA

William and Mary lived exclusively in Brooklyn where the Blazos ran their successful real estate and construction businesses. They had an apartment on Classon Avenue in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. It was a four room flat, modestly furnished with two bedrooms, a small kitchen and a good sized parlour with a large bay window that overlooked the street two stories below. The construction company prospered during the 1880s and at the end of the decade, Blazo had profited greatly from the construction of Brooklyn's Amphion Theatre. It was a sign of the times that as their wealth increased, the Blazos began looking for a place in the country and eventually purchased Graylock Villa. The Brooklyn apartment was kept because William would frequently come into the city and stay there while supervising large construction projects. He also remained on the board of trustees of Memorial Hospital and would return to Brooklyn for meetings of the board. Mary continued to use the apartment when she came into the city for shopping, visiting friends, or attending charitable events for the hospital.

After the Civil War, the wealthy elite left the city for their summertime “cottages” in Newport Rhode Island and the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. The Berkshires’ appeal was its quiet towns versus the city’s bustle, its lack of dirty, noisy manufacturing, and its easy access to Boston and New York. The opulence and the luxury of the Gilded Age showed in the beautiful estates and summer mansions, which were occupied for only a few weeks each year.

In April 1893, the Blazos bought Greylock Villa in western Massachusetts (near Pittfield). Built in the 1860s, it was called one of the finest residences in town and had cost $28,000 (about 1 million dollars today) to build. W.A.Blazo was now one of the town’s largest taxpayers, paying $112 yearly. The grounds of Graylock Villa were well-shaded by a variety of trees and were ideal for croquet.

In 1894, A.W. outfitted the mansion to accommodate 45 city guests such as C.C.Martin, Superintendent of the Brooklyn Bridge. Outdoor art classes were offered. The Villa was advertised as a health resort.

There were many social events held at Graylock. “A reception

was given by Misses Blazo Friday evening at Greylock Villa in honour of their

relative Mr.Farnum who is from out of town.

The yard was very attractive from a general display of Japanese

lanterns.”

Blazo started a poultry business at Greylock. When the

chicken incubator was invented in 1892, Blazo bought one. In 1895, 1500 chickens were hatched this way,

although he lost 200. In 1896, he lost 65 of his finest ducks to some disease.

D. WHAT HAPPENED?? !!

In May 1893, less than a month after the Blazos had purchased the villa, economic panic hit the nation. The New York Stock Exchange lost 50% of its value, stock prices fell, 500 banks closed, 1500 businesses failed. Unemployment hit 35% in New York. There was another economic depression in 1896 when the silver reserves dropped. Some high-profile bakers committed suicide

In all probability, the Blazos had overinvested in real estate and owed money they could not repay. In 1896 the Blazos defaulted on their $10,000 mortgage and Greylock Villa was sold at auction for $3000.

($100,000 today). A.W. also sold off his team of horses.

A. Blazo, the father, who had been suffering many years from trifacial neuralgia (sharp shooting pain in jaw and gums) moved out of Greylock Villa and to Boston where he died from myocarditis senility on May 30, 1902.(age 73) His wife Mary Elizabeth, spent a few months in California, retuned to Providence to stay with her daughter; she died there on Dec 21, 1903.(age 63) She was buried in the Blazo family plot in the Milton cemetery, Massachusetts

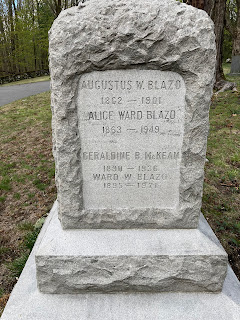

Augustus moved into Pittsfield where he worked as a foreman for a construction company. He moved to Brooklyn, then later to Boise, Idaho. Was it construction work that called him to Boise? No idea. A.W. died in Boise on January 8, 1902.(age 39) There were only two small death announcements in the eastern newspapers. There are no details on his burial. Is he also buried in Milton cemetery? Wife Alice outlived her husband by almost 50 years and lived with various of her children; she reported no income. Alice died March 6, 1949 (age 86) in Fairport, New York and is buried in the Milton Cemetery.

MARY ELIZABETH FARNUM

b. June 8, 1840 Hudson, New Hampshire

m. W.A. Blazo on Aug 23, 1858 in Milton, Massachusetts

d. Dec 21, 1903 in Providence, Rhode Island

my 3rd cousin 5x removed

(Homuth-Netterfield-Farnham line)

WILLIAM AUGUSTUS BLAZO

b. abt 1829 Parsonfield, Maine

d. May 30 1902, Boston, MA

SUMNER AUGUSTUS WILLIAM BLAZO

b. Mar 26 1862 Milton, MA

m. Alice Ward Aug 3, 1889 in King’s, NY

d. Jan 8 1901 in Boise, Idaho

my 4th cousin 4x removed

ALICE M WARD

b. June 1863 New York

d. Mar 6 1949, New York

Three weeks ago, en route to Boston we took a side trip to Cheshire to find Blazo's Greylock Villa. It still stands, but its former glory has faded. We were fortunate enough to be invited into the house to see the downstairs rooms.

“Nobs”, “Swells” and “Hottentots” these words all brought a smile to my face. Also, 1% of the wealthiest people in the US mostly likely still own a very large proportion of real estate so not that much has changed in that regard.

ReplyDelete